Cormac McCarthy is, according to many, one of the greatest living American writers of fiction. Based on his work that I’ve read in the past, I’m inclined to agree. He has published 12 novels. 2023, like most years, is expected to have 12 months. I will read one McCarthy novel each month, in publishing order, over the course of this year. Welcome to Cormac McMonthly.

Folks say he done but he never.

I can’t get these seven words out of my head.

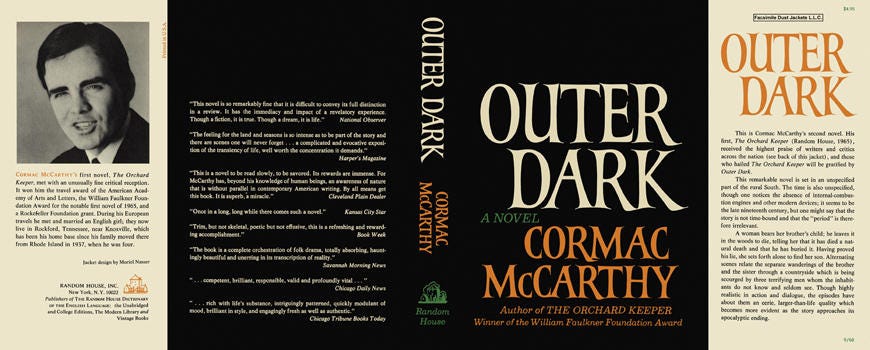

They occur somewhere around the middle of McCarthy’s second novel, published in 1968, and are emblematic of the kind of dialog this book is full of. If you can jive with this sentence, and all of the compact and complex beauty it contains, you might find a lot to like in Outer Dark.

That being said, if you’ve read Outer Dark, you may be surprised by the fact that these seven words, of all things, are what have stuck with me. This story contains horrors. It’s bookended by two of the greatest sins you can imagine—atrocities of the biblical variety, as old as humanity, and still as shocking to read about today as they ever have been.

And yet when I think back on my time with this book, those moments aren’t what first spring to mind. Between its stomach-churning opening and its blood-chilling conclusion, Outer Dark is, weirdly, a sort of homespun, ramblin’ road comedy. Almost of the buddy variety, except the buddies are never together in the same scene. Their lives run parallel to one another.

The novel opens with a poor young couple waiting for their baby to be born. They don’t wait long. They’re out in a cabin in the woods somewhere, and the man has refused all medical attention. The baby’s born healthy, but the man sees fit to leave the screaming newborn in the woods, much to the woman’s ire. She doesn’t find out about this abandonment until much later, though, because he tells her that the baby died in birth. But the baby doesn’t die. Instead, it’s found by a strange vagabond peddler, who will presumably help nurse the baby back to health.

That’s all horrifying in and of itself. What makes it especially difficult to bear, however, is the fact that the mother and father are sister and brother.

None of this is spoiler territory. It all takes place within the book’s first chapter.

I suspect that a lot of people bail on this book by the end of that chapter, and who can blame them? It is a shame, though, because much of what follows is an effortlessly readable journey in which the sister, Rinthy, and the brother, Culla, encounter a cast of memorable Appalachian oddballs. Culla’s on the run because he’s an incorrigible loser with poor judgment and worse luck. Having committed the sin of incest, he goes on to, among other petty crimes, swindle unsuspecting people out of money, food, and a very fine pair of boots. Meanwhile, Rinthy’s after Culla, as well as the man who took her baby, for obvious reasons.

See, what you might not expect from a book called Outer Dark, which begins the way it does, and contains all of McCarthy’s signature corruption, is for it to be so frequently amusing. Most of the characters Culla and Rinthy meet along the way are some combination of charming, reclusive and ridiculous. We’re never told which part of the world is the setting for this story, but ‘Appalachian’ feels accurate, from the distances travelled in between the shacks and meagre townships, and from the delightful (at least I find it delightful) dialect spoken by just about every character.

Folks say he done but he never.

If you can feel the rhythm with which these words would have been said, then you can hear the music hidden in this book. The dialog sings, and there’s a lot of it. And that is the biggest departure from McCarthy’s first novel, The Orchard Keeper, which was published two years before this one. The second biggest departure is that Outer Dark is structured like a typical narrative.

If The Orchard Keeper feels like being lost in the woods just outside of civilization, then Outer Dark feels like being a passenger on a very bumpy covered wagon ride, surrounded by well-meaning but cursed country bumpkins.

In The Orchard Keeper, McCarthy established his affinity for petty men shirking responsibility at every turn and being pursued by forces much bigger than them. He staked his territory, which is located somewhere between the Old Testament and Southern Gothic. Then, in Outer Dark, he ironed out his ability to tell a sprawling, propulsive and frequently troubling story, and he gained absolute mastery over dialog.

Folks say he done but he never.

That’s the one kind of McCarthy sentence. He doesn’t only excel at dialog, though. Here’s an example of the other kind of McCarthy sentence:

He rose and went on until he reached the gap in the ridge and before long he could see the first of them coming along the road below him and then suddenly the entire valley was filled with hogs, a weltering sea of them that came smoking over the dusty plain and flowed undiminished into the narrows of the cut, fanning on the slopes in ragged shoals like the harried outer guard of schooled fish and here and there upright and cursing among them and laboring with poles the drovers gaunt and fever-eyed with incredible rag costumes and wild hair.

Whew.

Guy’s good.

In the world of Outer Dark, McCarthy seems to be having fun, pointing out humanity’s complete idiocy in the face of nature—we’re just utterly unequipped to deal with it, and yet we persevere in trying. There’s something profoundly funny in that.

The darkness is all around us—it is ‘outer’ in this sense. It lurks at the edges of everything. Every action we take that isn’t actively harmful, if we’re lucky, only succeeds in pushing that darkness away for a brief moment in time. And so it is worthwhile to at least attempt to do good. That is a timeless truth.

If there is a most famous quote from Outer Dark, it’s this one. It could be the book’s thesis statement, or it could be something you or I might have muttered last Tuesday:

Hard people make hard times. I've seen the meanness of humans till I don't know why god ain't put out the sun and gone away.

Let’s you and I keep trying to keep the dark at bay.

Cormac McMonthly

January: The Orchard Keeper (1965)

Great review.

I was also struck by how funny this novel was, even though it's quite a bit darker than The Orchard Keeper. But I think you really nailed how great McCarthy's dialogue is. He has a strong ear for the music of language, which is, to me, among the most important things in writers.